On 16th November 1995, school

girl Leah Betts died at her 18th birthday party. She and a friend –

like many 90’s teenagers - had decided to take ecstasy, a drug which they had

both taken before with no ill effects. Popular advice for ecstasy users at the

time was to drink plenty of water and to stay well hydrated to avoid

overheating, so when Leah started to feel unwell she followed that advice. Leah

continued to feel unwell, so, thinking she was dehydrated, she continued to

drink water. Unfortunately for Leah and her family this harm reduction advice was

misguided and her consumption of too much fluid led to the water intoxication

that ultimately killed her[i].

On 16th November 1995, school

girl Leah Betts died at her 18th birthday party. She and a friend –

like many 90’s teenagers - had decided to take ecstasy, a drug which they had

both taken before with no ill effects. Popular advice for ecstasy users at the

time was to drink plenty of water and to stay well hydrated to avoid

overheating, so when Leah started to feel unwell she followed that advice. Leah

continued to feel unwell, so, thinking she was dehydrated, she continued to

drink water. Unfortunately for Leah and her family this harm reduction advice was

misguided and her consumption of too much fluid led to the water intoxication

that ultimately killed her[i].

Leah’s death caused a moral panic and a media storm about

ecstasy, with many overlooking the actual cause of death and blaming the drug

itself. Bad advice and confusing messages were partly to blame for the actions

she took after ingesting the drug, and whilst Leah would undoubtedly have lived

had she not taken ecstasy that night, the popular harm reduction advice that

was in the public domain at the time was undoubtedly a contributing factor.

Since Leah’s death, what little official harm reduction advice

there is has been amended to reflect the dangers of both overheating and overhydrating:

‘Users

should take regular breaks from the dance floor to cool down and watch out

for any mates who are on it – they mightn’t realise they're in danger

of overheating or getting dehydrated…’

‘…However

drinking too much can also be dangerous…Users should sip no more than a pint of

water or non-alcoholic drink every hour.’

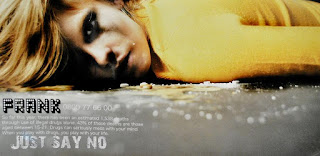

‘Ecstasy’, FRANK[ii]

With the rest of the ‘Ecstasy’ section of the FRANK website

emphasising either the associated illegalities or potential risks, it is clear that

there has actually been a shift away from harm reduction to prevention when it comes

to substance use education.[iii] Furthermore, the evidence seems to

suggest that despite many young people citing them as a source of information,

drug education initiatives such as the FRANK campaign fail to change behaviour.[iv]

|

| A news report on the death of Leah Betts |

So what has happened to a ‘forewarned is forearmed’ approach

in the substance use agenda? Martin Barnes from Drugscope is concerned about

the lack of harm reduction knowledge among the current ecstasy-taking cohort:

“Much of that knowledge

[about reducing harm], for example, not increasing dosage and not allowing the

body to get over-heated is less known to many of the current generation of club

and festival goers. We need to find ways of reminding young people about this

type of information, not only in relation to ecstasy, but also to the many

other new drugs now available.”

Martin Barnes, quoted in the

Independent, August 2013[vi]

Both Harry Shapiro (also from Drugscope)

and Professor David Nutt (Imperial College) agree that there is a worrying

political shift away from harm reduction because the media have helped create

such a moral panic that the issue of substance use is now rooted in a culture

of fear rather than in providing effective and useful information to users.[vii]

Whilst harm reduction interventions such as needle exchanges and methadone

clinics are still used in the treatment of harder drugs, the ‘softer’

educational harm reduction approach and the associated safety benefits continue

to be overlooked due to the controversial, emotive and political nature of

substance use legislation.

Current UK drugs policy has indeed seen a general shift

towards focusing on recovery and abstinence in recent years rather than on

damage limitation for substance users,[viii]

and the very mention of harm reduction as a tactic for tackling substance use

tends to send the more politically conservative into a moral spin as such

advice is seen to condone illegal and harmful activities. The “if you are going to do it, at least be

informed about it”[ix] approach to the so-called ‘war on drugs’

is frequently misinterpreted as condoning substance use, but if we accept that

prohibition has not eradicated these behaviours, the next logical step surely has

to be effective harm reduction advice. Moral panics and illegalities haven’t

stopped people taking ecstasy and other substances, so perhaps it is time to

educate people on how to stay safe, how to keep their friends safe, and on how

to reduce the potential harm involved in such activities. Settings in which

substance use tends to occur (such as festivals and nightclubs) should be free

to offer advice on safety without the fear of being seen to condone usage,

giving people the right information on how to manage dosage and dealing with any

associated concerns. Whilst we obviously don’t want to actively encourage drug

use, we do need to accept that certain behaviours exist in society, regardless

of whether they are either illegal or socially unacceptable.[ix] The challenge then shouldn’t be how we can

eradicate drug use, but how we can

ensure that harm reduction advice is freely available, easy for users to

understand and above all evidence-based; because the consequences of bad harm reduction advice can be as

devastating as having none at all.

[i] Henry,

J.A. (2000) Metabolic consequences of drug misuse. British Journal of Anaesthesia [online]. 85 (1), pp.136-142.

[iii] Measham, F.,

Williams, L. and Aldridge, J. (2011) Marriage, mortgage, motherhood: What

longitudinal studies can tell us about gender, drug ‘careers’ and the

normalisation of adult ‘recreational’ drug use. International Journal of

Drug Policy [online]. 22 (6),

pp.420-427.

[iv] Aldridge, J. (2008) A hard habit to break? A role for

substance use education in the new millennium. Health Education [online]. 108 (3), pp.185-188.

[vi]

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/fresh-fears-over-ecstasy-substitute-pma-after-rise-in-deaths-8787783.html

[vii]

http://www.mixmag.net/feature/ecstasy-in-2015

[ix]

Truss and White. (2010). Ethical Issues in Social Marketing. In: French, J. (2010) Social

Marketing and Public Health: Theory and Practice [online]. Oxford University Press.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteWell said Ms Beardmore.

ReplyDelete